History of Glacier Girl

As “Europe first” was the policy declared by then President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Operation Bolero began its phase in history as a massive buildup and movement of Allied aircraft into the European theatre. It was Tuesday, July 7, 1942, just seven months since the attack on Pearl Harbor that had thrust the U.S. into the war.

The most daring aspect of Operation Bolero was the actual flight overseas in stages, refueling in Labrador, Greenland and Iceland. Only the second of many flights to come during this operation, none of the pilots of what has now become known as “The Lost Squadron” knew their flight to England would end on the ice cap in Greenland.

By early morning on July 15, 1942, Tomcat Green and Tomcat Yellow, both squads consisting of Lockheed P‑38s escorting a Boeing B‑17 were airborne again, on their way to Iceland. This leg of the trip would take the squadron southeast over the ice cap and the mountains of the east coast of Greenland, then across the Denmark Strait to Reykjavik, Iceland.

By early morning on July 15, 1942, Tomcat Green and Tomcat Yellow, both squads consisting of Lockheed P‑38s escorting a Boeing B‑17 were airborne again, on their way to Iceland. This leg of the trip would take the squadron southeast over the ice cap and the mountains of the east coast of Greenland, then across the Denmark Strait to Reykjavik, Iceland.

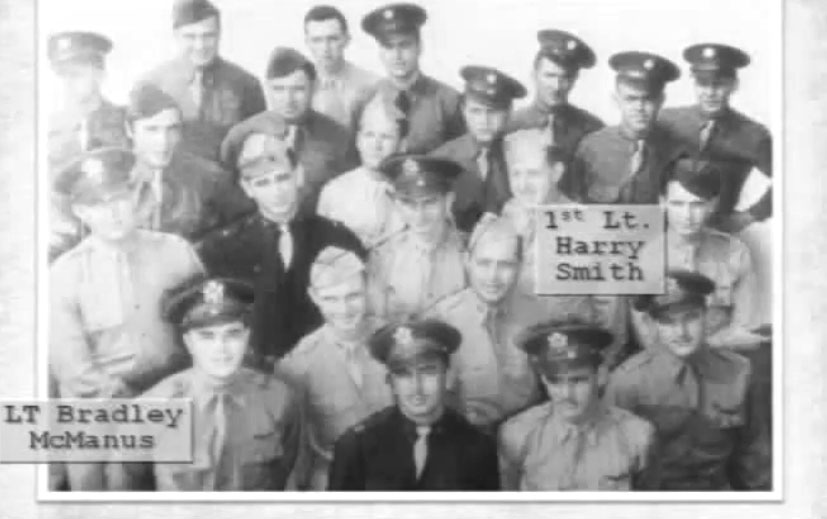

As the squadron soared across the ice cap at twelve thousand feet, a heavy blanket of clouds began to form. They rose above it where the temperature dropped to minus ten degrees Fahrenheit. Ninety minutes from Iceland, the planes hit a mass of cumulus clouds, forcing them to climb another two thousand feet. The pilots resorted to various means of trying to keep warm. R.B. Wilson had impulsively torn the defroster from its mounting and was using it to heat his gloves in an effort to keep his hands warm enough to feel the controls. Brad McManus, a then surviving member of the squadron (McManus passed away on March 21 2011) visualized his parents sitting in bathing suits on the beach. His feet were so cold he could barely feel the rudder pedals.

Desperate to find better flight conditions, Spider Webb radioed he was taking Tomcat Green down to look for clear weather beneath the overcast. The clouds closed in above them as they dove through the murky skies. In a matter of minutes they were in what was described as clouds dense as cotton drenched in tar.

With ice forming on the wings and the P‑38s struggling to maintain contact with the B‑17, Wilson ordered the bomber to climb out of the mess. At sixteen thousand feet, Tomcat Green broke through the clouds and rejoined Tomcat Yellow. They didn’t know which was worse, flying in the snow storm or watching your own skin turn blue at higher altitudes. They were only an hour away from Reykjavik, but another massive front lay ahead.

After flying south for another fifteen minutes trying to find a way around the front, pilot Joe Hanna of the B‑17 reported his radio operator was unable to raise either Reykjavik or a weather plane supposed to be flying an hour ahead. At 7:15 a.m. it was decided the squadron should turn back and head for BW‑8, the airbase on the western side of Greenland from where this leg of the flight originated.

An hour later, they saw the east coast of Greenland and weather that would prove to be as bad or worse than they flew through earlier.

About 130 miles from the base the B‑17s apparently received a message from BW‑8 that said “Ceiling twelve hundred feet. Visibility one-eighth mile”. McManus and several other P‑38 pilots decided to go down and take a look at the ice cap, in case they had to make an emergency landing. After rejoining the squadron between the layered clouds, it was reported the B‑17s had received a message from BW‑1 at the southern tip of Greenland, that its runway was open. It was 10 a.m. Estimated time of arrival would be noon. Officials later compared Allied weather records to the coded messages and discovered the reported weather conditions at BW‑8 and BW‑1 had been switched. (Speculation of radio interference from Nazi U‑boat or secret radio station was never proven.)

After ninety minutes of flying through dense cloud cover, the coastal mountains appeared through an opening. But where on the west coast were they in relation to BW‑1? They soon discovered they were back on the east coast of Greenland, two hours away from BW‑1. McManus’s fuel would only last another twenty minutes.

He didn’t think there was a serious fire threat, as his tanks were almost empty, but he wasn’t sticking around to find out. McManus managed to kick and dig his way out of the cockpit onto the ice.

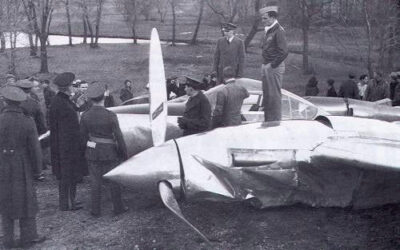

From the air, Robert Wilson viewed the scene and retracted his landing gear. He came down and slid to a smooth stop and raced the almost half-mile to McManus’ plane to see if he was injured. When he reached it McManus came out from under the wing and said “Well, Egghead, didn’t think I’d make it, did you?”. They turned and waved to the pilots above, who responded by doing slow rolls and other acrobatics.

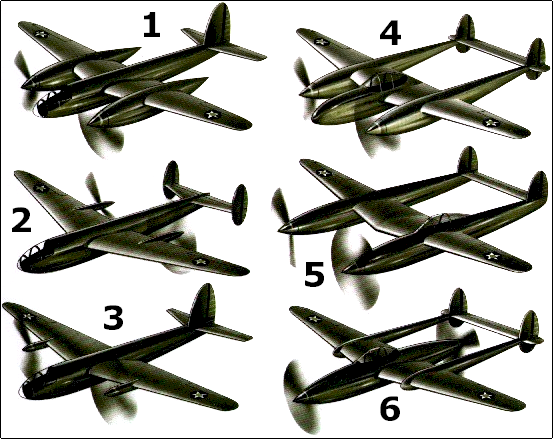

One by one the other P‑38 pilots brought down their planes, as the two B‑17s remained aloft for another half hour, expending their remaining fuel. It was the largest forced landing in Air Force history, even today. This is an aerial shot of the six P‑38s on the glacier.

Having made successful landings, the job at hand was survival and rescue. Rations were gathered and divided to last two weeks. Warnings were issued not to eat excessive amounts of snow (to prevent sore throats) and to wear sunglasses at all times to prevent snow blindness. Space heaters were made from empty oxygen bottles with holes hack sawed in both ends and linked to an engine manifold pipe. Oil drained from the engines wicked through the device by means of parachute straps.

After three days on the ice, a Morse code message received by one of the radio operators confirmed their condition and position. Later that day two C‑47 transport planes dropped supplies by parachute only to see them carried out of sight by strong winds after they hit the ground. The stranded airmen fanned out as the planes made additional drops and managed to smother the parachutes before the wind again took their supplies to the far horizon.

Supplies had arrived and everyone breathed a sigh of relief. They passed the time listening to music and news picked up on the radio from Iceland and England. They even had an impromptu square dance on the wing of one of the B‑17s.

Another favorite pastime was to ride the wind using parachutes to pull them along while sitting on burlap sacks. More supplies were dropped in the following days as rescue efforts had begun in earnest.

A 30-foot wooden launch, the Uma Tauva, was dispatched from BE‑2 to get the airmen off the ice. (Among those onboard was Donald Kent, son of famed American painter Rockwell Kent, acting as an “arctic adviser”). After landing ashore and with assistance from aircraft flying overhead, the ski and dogsled team were guided through 17 miles of zigzagging crevasses to reach the stranded airmen.

At the crash site, preparations were being made to move out. The P‑38 pilots returned to their planes to retrieve personal effects. Some fired .45 slugs into electronic equipment in case Nazi scavengers descended on the site. McManus removed the clock from his instrument panel as a keepsake. After all necessary gear was packed and ready for transport, the rescue team appeared and prepared the men for what would prove to be an exhausting hike out.

Loaded down with equipment and personal effects, members of the squadron struggled through knee deep snow and ice for hours before reaching the edge of the cliff at the ocean’s edge. After reaching the beach, most of the exhausted men found a suitable spot to curl up and get some well deserved sleep.

Harry Smith was the pilot of “Glacier Girl” and Brad McManus was, as mentioned above, the first pilot who landed on the glacier, wheels down.

Several hours passed before the Coast Guard cutter Northland arrived. After boarding, they were treated to showers, dry clothes and an extravagant navy meal. They were finally returned to BW‑1 where they were debriefed and later sent back to the U.S. to new assignments.