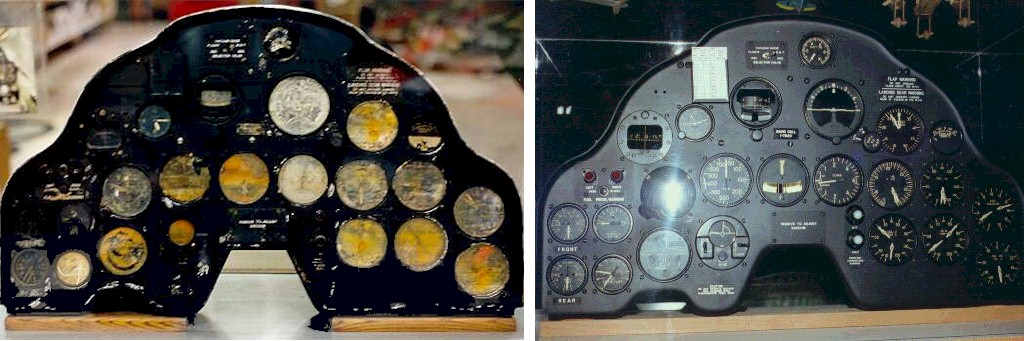

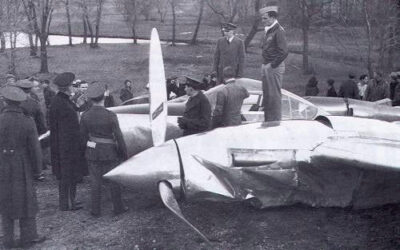

Before the Rebuild…

Restoration of Glacier Girl began in January of 1993, after all shipments of aircraft parts from the dig were finally gathered together.

The restoration was being done in Roy Shoffner’s (project financier) hangar in Middlesboro, Kentucky. Under the supervision of Bob Cardin (project coordinator for the 1992 expedition) warbird specialists began their task by disassembling the massive center section.

After initial deconstruction of the plane began, it was evident that damage was more extensive than what appeared on the surface. The more they took apart, the more damage they found.

After initial deconstruction of the plane began, it was evident that damage was more extensive than what appeared on the surface. The more they took apart, the more damage they found.

The plane had to be taken apart down to the smallest manageable pieces, making sure each piece was marked for later identification. Parts were then cleaned and checked for functionality to determine if it could be used again, repaired for use, or replaced entirely. Damaged parts served as templates for construction of replacements.

Aiding in the process of restoration, an extensive research library was compiled. For research and copy fees of $1,200, the Smithsonian Institution supplied eight reels of microfilm and stacks of photocopies of era aviation maintenance handbooks, parts and repair manuals. Cardin’s team, using the acquired documents, managed to more or less duplicate the original construction process carried out in the 1940s.

Rebuilding Glacier Girl

Spring of 1993 saw the beginning of actually rebuilding the plane, the main spar being the starting point. Clicos — temporary fasteners resembling bullets — were used so parts could be attached and removed to ensure proper fit and to be certain no pieces were overlooked.

Parts were much cheaper to acquire than creating molds to fabricate new ones. Finding them proved to be another adventure in itself. Cardin said he and Shoffner had visited people who claimed to have P-38s, only to discover unrecognizable piles of aluminum that wouldn’t pass as airplane parts. They felt like they spent more hours playing detective than actually acquiring parts. Even when parts were located, owners were reluctant to part with them.

In one case, Cardin found a needed set of engine cowling replacements, only to be told he would trade them for a Wright 1820, a rare model of aircraft engine. Cardin found one, traded for that engine and then traded for the cowlings. Another part needed was a control yoke. After several months search Cardin found one, but the owner was unwilling to part with it. Cardin’s persistence, along with a little luck, finally led him to a warehouse where he found two hundred of them. The owner of the warehouse didn’t realize what they were!

Interested parties also donated their expertise in goods and services to the project. Companies such as B.F. Goodrich Aerospace in England rebuilt the landing gear and brakes, and a Pennsylvania company fabricated a new canopy. An aviation mechanic volunteered to rebuild the Allison engines for the cost of parts. The electrical system was replaced in the same manner.

When this project was completed, Glacier Girl was one of the most perfect warbird restorations ever. “This is going to be the finest P-38 in the world, and it may be the finest restoration of any warbird ever done,” said Cardin.

Work completed, thousands of people, from veteran aviators and aviation buffs to curious onlookers, come to a hangar in Middlesboro, Kentucky, to see a not-so-forgotten piece of history.