Sleek, Fast and Luckless

– Time Magazine, Feb 20, 1939

– Time Magazine, Feb 20, 1939

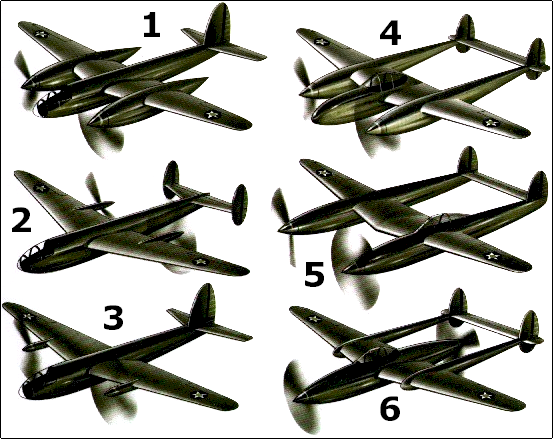

She was sleek as freshly peeled willow. As overalled mechanics trundled her out for the warm-up at March Field one day last week she gleamed slimly among the bulb-nosed fighters, the potbellied bombers on the Army Air Corps Southern California airdrome. Major General Henry H. Arnold, greying Chief of the Air Corps, surveyed with particular approval her twin engines, Prestone-cooled V12 Allisons of 1,000 horsepower each, faired trimly into the metal wing. Well he knew that broad-beamed radial air-cooled motors, such as the big U. S. engine builders have brought to perfection, could not be used on such a ship without protruding in speed-killing humps on the wing’s leading edges, that only the Allison (TIME, Jan. 30) could do the job cut out for the new fighter.

When the engines had been warmed up, Lieutenant Ben S. Kelsey, one of the Army’s ace test pilots, buckled his parachute leg-straps, climbed into her independent midships compartment (she is twin-tailed) and took off. Half an hour later he landed, and delighted Henry Arnold issued a statement to the press about XP-38, the Air Corps’s break from pursuit tradition. The ship, said he, “opens up new horizons of performance probably unattainable by nations banking solely on the single engine arrangement.” Kelsey had traveled more than 350 miles an hour in the test. He was satisfied the Lockheed was highly maneuverable, had more than 400 miles an hour in her.

Day after the test, Ben Kelsey took the ship East, stopped 22 minutes at Amarillo for fuel, lost another 23 minutes at the gas pit in Dayton. When he whipped over Mitchel Field on Long Island, just as the sun was setting, he was seven hours, 45 minutes (elapsed time) out of March Field, 2,400 miles away, and only 17 minutes slower than Howard Hughes’s record non-stop transcontinental flight in a racing plane in 1937.

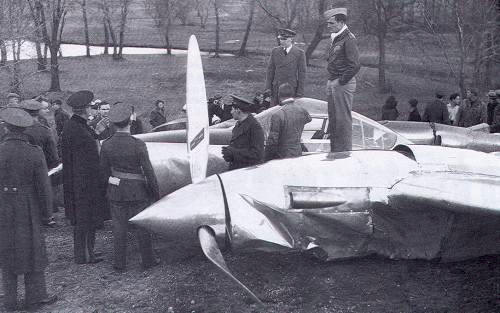

Swinging swiftly in a wide arc he squared away for a landing, let down his landing gear. Then came some more of the sort of bad luck that has dogged new Army ships of late. As Pilot Kelsey suddenly realized that he was falling short, he opened his throttles to drag into the field. Without so much as a cough his left engine died. Plowing her wheels through a tree, the XP-38, with right engine throttled, slammed into the sand bunker of a golf course, came to a stop with her right wing torn off, her props hopelessly snaggled, her fuselage twisted (see cut). A passing motorist helped dazed Ben Kelsey from the wreck. He had been only slightly cut. (See another photo at bottom of page.)

Probably damaged beyond repair was XP-38. But in the Lockheed factory, at Burbank, Calif., were all the drawings, dies and jigs needed to make many more like her. Pilots said the twin-engined pursuit ship had joined the Air Corps.

“Mystery” Plane Crashes At End Of Test Speed Hop; Fails to Break Hughes Mark

– Associated Press, New York, February 11 (1939)

A new secret twin-motor Army pursuit monoplane crashed into a tree on the edge of Mitchel Field on Long Island tonight at the end of a near-record transcontinental test flight.

The pilot and sole occupant, Lieutenant Ben S. Kelsey, crack test flier, was saved from serious injury by the plane’s all-steel cabin.

Kelsey took off from March Field, Calif., at 9:12 a.m. (Eastern Standard Time), stopped briefly at Amarillo, Texas, and Dayton, Ohio, and arrived here at 4:57 p.m. His elapsed time of 7 hours 45 minutes was only 16 minutes and 35 seconds longer than Howard Hughes’s 1937 Burbank, Calif.-Newark, N.J. nonstop record.

He apparently overshot the field, observers said, and zoomed the motors to pick up speed and altitude. The right motor appeared to choke, sending him into a steep right turn.

As Kelsey cut the throttle again, the plane slipped down and sheared off the tops of trees bordering the field, the undercarriage caught in a thirty-five-foot tree, and the plane plunged down into a sand pit on the Cold Stream Golf Course.

Bystanders pulled Kelsey out of the wreckage. He was taken to a hospital with cuts on one eye and one hand, and suffering from shock. He was released after examination.

Scores of cars jammed around the spot. Field officials threw a fifty-man guard around the wreckage and rushed the plane’s instruments to the field office, their condition undetermined.

Colonel James Chaney, field commandant, called an inquiry board into session immediately, with Kelsey present. The findings were expected to be kept secret and sent to Washington in an army plane.

The weather at the time of the crash was clear, with a light shifting wind. At the time of the crash it was blowing southeast.

The plane was a new Lockheed, the Army’s first twin-engined pursuit plane, completed at the Lockheed Burbank plant two weeks ago and capable of doing 350 miles an hour.

It was an all-metal single-seater, with stratosphere operating equipment, tricycle undercarriage, and super-high lift devices.

It was designed to carry a nest of high-power machine guns, but none today. Its designation was XP-38.

Kelsey left Amarillo at 12:21 p.m. (E.S.T.), stopped at Dayton for 20 minutes, and took off at 3:34 p.m. (E.S.T.)

His distance was estimated officially at about 2,400 miles. Hughes flight was about 2,587 miles.

Kelsey, 33, is married and is regularly assigned to the laboratory division of Wright Field, Dayton.